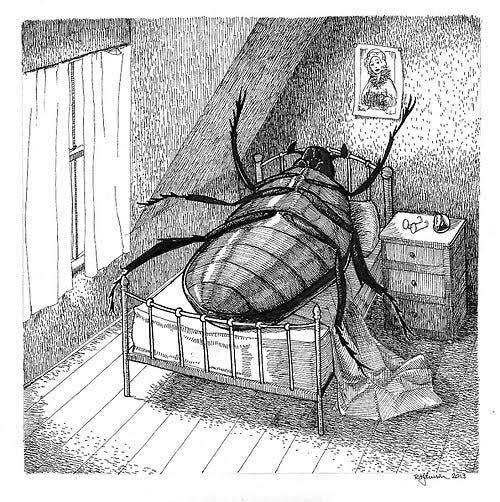

In the opening lines of Franz Kafka’s 1915 novella, The Metamorphosis, readers are confronted with one of the most jarring sentences in literary history:

“As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect.”

With this matter-of-fact delivery, Kafka bypasses the “how” of the supernatural and dives straight into the “why” of the human condition. The story is not a horror trope about a monster; it is a profound exploration of alienation, the crushing weight of capitalism, and the fragility of familial love.

The Burden of Utility

Before his transformation, Gregor Samsa’s identity was entirely subsumed by his role as a traveling salesman. He was the sole provider for a family that had grown comfortably stagnant on his labor. Kafka highlights the exhaustion of this existence:

> “Getting up early all the time… it makes you stupid. You’ve got to get enough sleep.”

Once Gregor becomes a “monstrous vermin,” his tragedy isn’t just his new physical form—it is his immediate loss of utility. His manager doesn’t offer sympathy; he offers accusations of poor performance. His family doesn’t see a suffering son; they see a financial liability.

The Dissolution of Sympathy

The most heart-wrenching arc of the novella is the transformation of Gregor’s sister, Grete. Initially his only advocate, she eventually leads the charge for his disposal. This shift illustrates a brutal truth: unconditional love often has a shelf life when faced with a burden that offers nothing in return.

By the end, Grete exclaims:

“It has to go… that’s the only way, Father. You’ve got to get rid of the idea that that’s Gregor. Our real misfortune is that we believed it for so long.”

This rejection is the final blow. Gregor’s physical death is merely a formality; his social and emotional death occurred the moment he could no longer work.

Kafkaesque Reality

The term “Kafkaesque” is often used to describe bureaucratic nightmares, but in The Metamorphosis, it refers to the surreal feeling of being trapped in a system that is both nonsensical and inescapable. Gregor feels guilty even as he is dying, proving how deeply he had internalized his role as a servant to others.

Kafka once wrote in his diaries:

“I am separate from all things by a hollow space, and I do not even reach to its boundaries.”

This sentiment is the heartbeat of the novella. Gregor is physically confined to his room, but he was emotionally isolated long before his legs became numerous and spindly.

ConclusionThe Metamorphosis remains a masterpiece because it mirrors our deepest fears: that we are only valued for what we produce, and that should we “break,” the world—and even those we love—will eventually move on without us. Gregor’s quiet passing, followed by his family’s upbeat outing to the countryside, is perhaps the most chilling “happy ending” in literature.

Here are some books with themes or styles similar to The Metamorphosis — surreal transformations, existential angst, alienation, or absurdist perspective

Bohumil Hrabal – “Closely Watched Trains” – Dark humor and human absurdity in wartime.

J.M. Coetzee – “Waiting for the Barbarians” – Psychological isolation and societal critique.

Samuel Beckett – “Molloy” – Deeply existential and fragmented interior monologue.

By: Mihir Vaishnav